Here’s Just A Few Of The Horrifying Things That Medical Students Believe About Black People

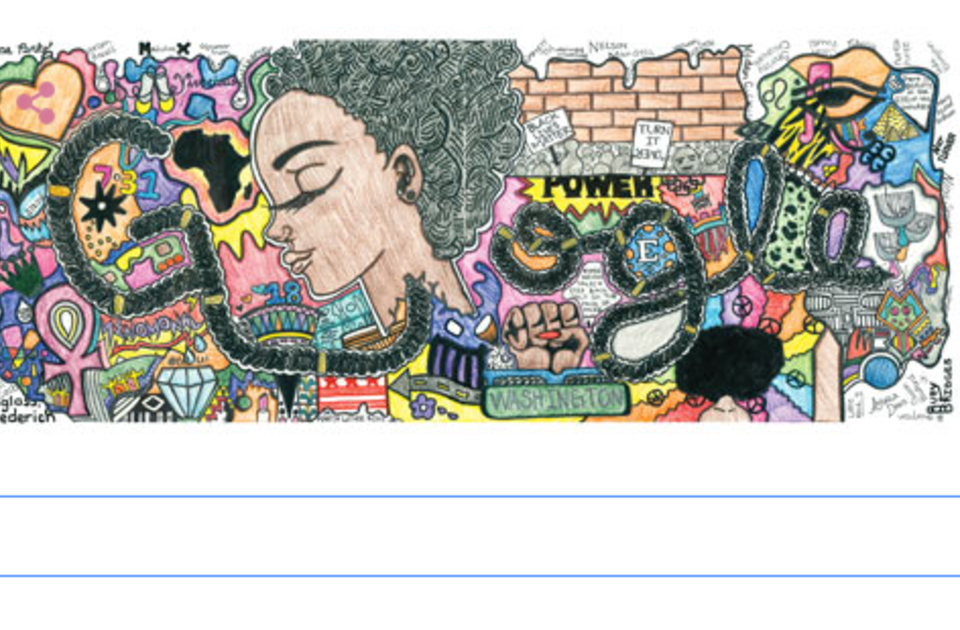

This Stunning Pro-Black Google Doodle Was Created By A 15-Year-Old

April 17, 2016

Watch the first (and only!) African-American grandmaster teach life lessons through chess.

April 18, 2016Here’s Just A Few Of The Horrifying Things That Medical Students Believe About Black People

Racism and racial inequality are, ludicrously, still alive and sometimes thriving within societies, and the U.S. is no exception to this. From the enormous wealth gap and off-the-cuff offensive remarks to far more deadly acts, America has a deeply-entrenched problem that has spread across all sectors of society.

A new study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences has revealed that even the medical world hasnt escaped racial stereotyping. Its widely acknowledged that black Americans are undertreated for pain relief compared to white Americans, and this study suggests that this could be because numerous medical students still believe that black people feel pain differently, among other completely false beliefs.

These beliefs have been around for a long time in our history.They were once used to justify slavery and the inhumane treatment of black people in medicine, Kelly Hoffman, a University of Virginia (UVA) psychology PhD candidate and lead author of the study, said in a statement. Whats so striking is that, today, these beliefs are not necessarily related to individual prejudice. Many people who reject stereotyping and prejudice nonetheless believe in these biological differences.

Hoffmans team asked 222 white medical students and residentsabout the pain thresholds of black patients relative to white patients. They were also questioned on various biological statements, demonstrably false, associated with black patients.

These included black peoples skin is thicker than white peoples skin, black people age more slowly than white people, and even white people have larger brains than black people. The researchers noted that the general public, who were also surveyed for this study, often held these erroneous beliefs.

Results of the survey. Study 1 featured 92 non-medical white people; Study 2 featured white medical students and residents. The bold statements are false, whereas the asterisked statements are factual. Hoffman et al./PNAS

Unfortunately, these thoughts clearly persist even among medical students. Some first year students think that black peoples blood coagulates faster than others. A group of second years thought that black people age more slowly. A small number of third years assumed black people are better at detecting movement than white people.

Even medical residents, those who have graduated and actively practice medicine, are not immune to false beliefs: Some of them thought black people have thicker skin than white people.

It is true that there are some medical differences between black and nonblack people. For example, black people do have denser, stronger bones than others overall; white people are less likely to have a stroke than black people. Black people are also less likely to contract spinal cord diseases. However, the fact that half of those surveyed endorsed at least one false belief is a cause for major concern medical students and especially residents should know better.

Following up these results, they asked all participants to decide on a level of pain that patients, black and white, may be experiencing in simulated cases (a leg fracture, for example). Participants who previously endorsed false beliefs were also more likely to underestimate the pain being experienced by black patients compared to white patients, and were also less accurate when suggesting treatment in the same respect.

This shows that medical practitioners’ false beliefs actively reduces their ability to do their job properly. Future work will need to test whether challenging these beliefs could lead to better treatment and outcomes for black patients, Hoffman concluded.